With the arrival of the open web, it was okay not to pay writers. And when you didn’t pay writers, you needed more of them. As an editor, perhaps you invited writers to contribute that you wouldn’t normally to increase page views. You weren’t serving the reader, you were serving the advertiser. Soon you had the Huffington Post, which at one point was the darling of the free and open web, with nary a question on the model, because the content was good.

Inspired by its decentralized technology, the open web was supposed to shift the power from the corporation to the people. Many imagined a sort of utopian society that relied on abundance instead of the current economy’s premise of scarcity. And the web did fulfill the promise of abundance in the form of Free, but utopia would have to wait.

With distribution came dislocation, and companies were able to use the web to extract more and more value out of the people creating the value. The same industrial model worked on the networked net because technology still favors efficiency over say, any other human value.

As a result, the most popular articles on the Huffington Post today read more like TMZ or People magazine: “Awkward Wedding Photos: Who Knew That Tying The Knot Could Be This Hilarious?,” “Khloe Kardashian Talks Weight: ‘Love Handles’ And ‘Fat Days’,” “Courteney Cox on ‘Strictly Platonic’ Vacation With Co-Star Josh Hopkins,” “’Dancing With the Stars’ Recap: Week Two Elimination,” and “Woman Can’t Close Her Eyes After Bungled Plastic Surgery.”

Not to mention, the advertisements on Huffington Post are indistinguishable from the content, and both are seemingly designed that way: “The Original Crime Family – The Borgias Premiere Sunday 9p e/p on Showtime.”

Whatever Arianna Huffington banked from that list of articles (ads?) allowed her the audacity to poke fun of the New York Times paid subscription model this past April Fools’ Day. To be fair, the post pokes fun at the New York Times and the Huffington Post simultaneously, declaring in jest that the Huffington Post’s move to digital subscriptions will be “one that will strengthen our ability to provide high-quality journalism to readers around the world.” (We’re all in on the joke; Huffington hasn’t valued high-quality journalism for a great while.) Later, Huffington facetiously describes HuffPo’s signature offering as an adorable kitten slideshow. Which isn’t far from the truth. In fact, a kitten slideshow might be an improvement on their most popular offerings.

Nevertheless, other sites have followed suit (if anything, the web excels at copying). Almost a year ago, Forbes.com announced that it would open the door “to 1000s of unpaid contributors and [rather than commissioning quality in-house journalism] ‘Forbes editors will increasingly become curators of talent,’” reported Tech Crunch writer Paul Carr.

Carr predicted that the Forbes decision would result in the magazine suffering the “Death of a Thousand Hacks,” which has two meanings: “The first, much like the death of a thousand cuts, is that they’re chipping away at everything they used to represent by replacing real reporting with SEO-driven bullshit and an army of unpaid amateur hack bloggers. The second meaning is that those thousand hacks are going to kill their brand.”

Since then, hundreds of bloggers received invitations to join Forbes.com including myself. The email I received implored me to “Just continue to do what you do best–write. I am not looking for exclusive content (although it’s most welcome), request copyright or ask that you blog any more than you already do. Forbes does not wish to control, alter or affect your blog in any way,” the editor told me. “You can publish simultaneously on your blog and your personal Forbes.com blog… As an uncompensated contributor, your posts will be available to millions of dedicated Forbes readers.”

To be clear, the editor is only requesting permission to copy my work onto the open web in exchange for increased exposure instead of compensation. I wouldn’t even have to be held accountable for blogging regularly. When I inquired about the possibility of a consistent, paid position, the editor replied: “Can I *promise* regular, consistent writing position? That’s something you can do with your blog. Which brings us to your next question: Can I *promise* paid writing at a later date? I can say it is a possibility.”

Her response seemed fair and promising. However, when I asked her to point me to any examples of any bloggers on Forbes that started uncompensated and were now paid, the editor came up short. “This is such a new platform that I honestly can’t,” she replied. Instead, the editor supplied me with the contact information of a writer she had to cut when she lost her freelance budget, but was now excited to bring back with “some compensation.”

I expect this would be no surprise to Carr if he heard. He argued Forbes would do “what the Huffington Post does: pay a meager stipend to a tiny percentage top traffic drivers to save face [indeed, Forbes admits this proudly], and then expect the rest to work ‘for the exposure’. As the old saying goes, people die from exposure – but in this case, it might just be the whole publication that’s not long for this world.”

Companies of formerly strong reputation take on the content farm model, and then editors have the job of throwing spaghetti on the cupboard to see what sticks. Forbes calls this curation, but I sensed a distinct desperation from the editor who emailed.

The value shift from core product to peripheral offerings on the free web means companies extract enormous amounts of value from writers who rely on the promise of monetizing their exposure, in the form of, say, speaking engagements or TV appearances, instead of their work.

“Of course, the people hiring us to do those appearances believe they should get us for free as well, because our live performances will help publicize our books and movies. And so it goes, all the while being characterized as the new openness of a digital society, when in fact we are less open to one another than we are to exploitation from the usual suspects at the top of the traditional food chain,” argues digital theorist Douglas Rushkoff.

“The very same kinds of companies are making the same money off text, music, and movies—simply by different means,” argues Rushkoff. “Value is still being extracted from everyone who creates content that ends up freely viewable online. It’s simply not being passed down anymore.” Writers aren’t being paid, but advertisers are.

The New York Times has thus refused such a model in the interest of creating value, not extracting it. Good journalism, after all, is expensive. It takes time, money, bodies, effort and significant resources. While it can be replicated by machine, it can’t originate from one.

The recent introduction of the New York Times pay wall however, did not inspire the valuation of content from readers, but a further alignment with corporatism.

“When we insist on consuming it for free, we are pushing them toward something much closer to the broadcast television model, where ads fund everything,” argues Rushokoff. “We already know what that does for the quality of news and entertainment. Yet this is precisely the model that the ad-based hosts and search engines are pushing for. By encouraging us to devalue and deprofessionalize our work, these companies guarantee a mediaspace where only they get paid. They devalue the potential of the network itself to create value in new ways.”

So eager are we to let advertising dictate the availability of quality content that the free and open web has only given us an abundance of copies. The aggregation of creative material and original thought has declined. No longer can we rely on corporate interests to create, sustain, build and evolve our platforms in a post-scarcity society. The solution, simply, is to value content, to respect the labor of individuals.

Lest you think such an approach is pie-in-the-sky, turn your attention towards The New Yorker, which “puts investigations of national security on the cover instead of celebs, yet it has the highest subscription renewal rate of any magazine in the country. A privately owned company, it is thought to be turning a profit of around $10m. Editorial decisions there are never made by focus groups,” reports Matt of 37signals.

If we want anything more than the most mediocre culture to survive, inform our consciousness and influence our future, writers deserve to get paid.

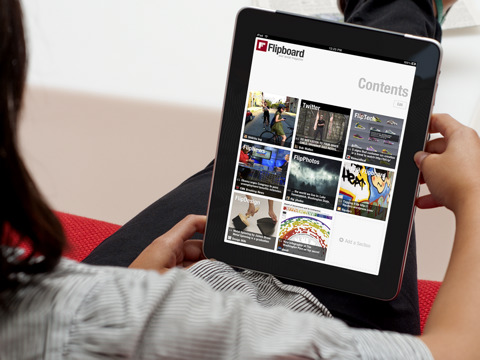

I just… the insanity of this… “Flipboard, the online news magazine app, has raised $50m at a $800m valuation, which is almost 50% of the market cap of The New York Times Company at $1.75 billion.” A near-billion dollar valuation?

I just… the insanity of this… “Flipboard, the online news magazine app, has raised $50m at a $800m valuation, which is almost 50% of the market cap of The New York Times Company at $1.75 billion.” A near-billion dollar valuation?